Portrait of a Palate: Karuna Long

Food as a means to preserve culture, nurture curiosity & return to self

Portrait of a Palate is a series of interviews exploring an individual’s relationship to food, how it’s shaped them, and how that relationship has evolved over the course of their lives.

Karuna Long is the chef and owner of Sophon, a Seattle-based Cambodian restaurant that honors traditional Khmer flavors while embracing the influences of the Khmer diaspora. In just one year, Sophon has become a standout in the Phinney Ridge community, earning a spot on Bon Appétit’s 2024 Best New Restaurants list and a 2025 James Beard Award semifinalist nod for Best New Bar. Its celebrated drink program showcases Karuna’s deep expertise, shaped in part by his experience leading nearby bar Oliver’s Twist, which he took over in 2017.

Stay up to date with Karuna on Instagram at @karu1001 and Sophon at @sophonseattle.

Note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

LINDSEY OTTO: How would you describe your relationship to food?

KARUNA LONG: My relationship with food is pretty passionate and built out of curiosity. I’ve always loved food and I’ve always been very adventurous with food. My brothers and I have always been the easy kids my mom had; we would eat and polish [off] everything. We’d try it and finish it. Only in my later years in life did I really fall in love with the culinary side of it. When I was a kid, I hated food from the cooking standpoint because our mom would always make us help prep and we’d rather have been playing outside. But we always loved eating her food.

Food is also comforting. What I mean by comforting doesn’t necessarily mean only my mom’s food and my culture’s food, but all the food I’ve experienced in my life. Things that remind me of different places I’ve grown up, different places I’ve visited, or different people that I’ve been fortunate to have as part of my life. We have either shared the communal table over food or conversation or something like that.

OTTO: Can you recall a specific meal or dish from your childhood that holds a special place in your memory?

LONG: There are two dishes that stand out the most to me. One is called mee katang in our culture and it’s essentially a wide rice noodle that’s wok fried. It’s similar to a pad see ew—but also not. I hate to say it in that context because a lot of folks don’t realize that Thai and Siam cuisine originated from the Khmer empire. There’s this whole history to it.

It’s one of my favorites because I love the way our mom makes it. She makes it a little different. Instead of it being gravy-laden, it’s a lot lighter on the gravy and she chars the noodles, so there’s a nice crisp to it. It’s so stereotypical to say it was made with love, but I feel like it was because she forced my brother’s and I to take part in making it. It was such a tribe-like event. When I’d want it, she’d say, “Ok, you separate all the rice noodles,” because they get all stuck together. Then, “You break the eggs and whisk them together.” It’s a labor of love. I really enjoy it and it is so comforting because it reminds me of all the different memories of the different times we helped her make it. Even though we hated helping her at that time.

The other dish was from when we were growing up in Georgia. Our mom was 19 when she moved to the States after the Khmer Rouge situation, and she and our dad started to get familiarized with different American foods. Spaghetti was a popular one. She would always replicate spaghetti but she would always make it with fish sauce and other Asian ingredients. It just always tasted good. People would knock me for it but she would also use a jar of Prego. You know, she’s making do with what she knows. She would dress it with julienne cucumbers, Thai chilis, and all these Asian toppings. This is the most Asian spaghetti I’ve ever had in my life, but it was so good and one of my favorite things I always think of.

OTTO: What was your kitchen like as a child?

LONG: Definitely clean, but zero organization. The kitchen was just madness when our mom was cooking. It was either she had us involved with it or it was her and a bunch of aunties and great aunts.

At the time we were growing up, my grandma—my mom’s mom—and her family were [here in Seattle], so for most of the places we [moved around to and] grew up in, she wasn’t really around. [We were] around my grandmother on my dad’s side, but she doesn’t really cook. Both sides don’t really cook at all.

This is why we saw aunties, great aunts, and a lot of close women to the family who we called aunties with our mom in the kitchen. Imagine a 6’x10’ space and you’re trying to squeeze in six-to-eight Khmer women and they are all sitting on the floor, mortar and pestle, standing around, doing this, shredding that. It was a lot of fun. In those circumstances, where the family is coming together for a large meal, oftentimes the girl cousins—I felt so bad for them—would be tasked with helping with all the prep and the boy cousins got to play outside.

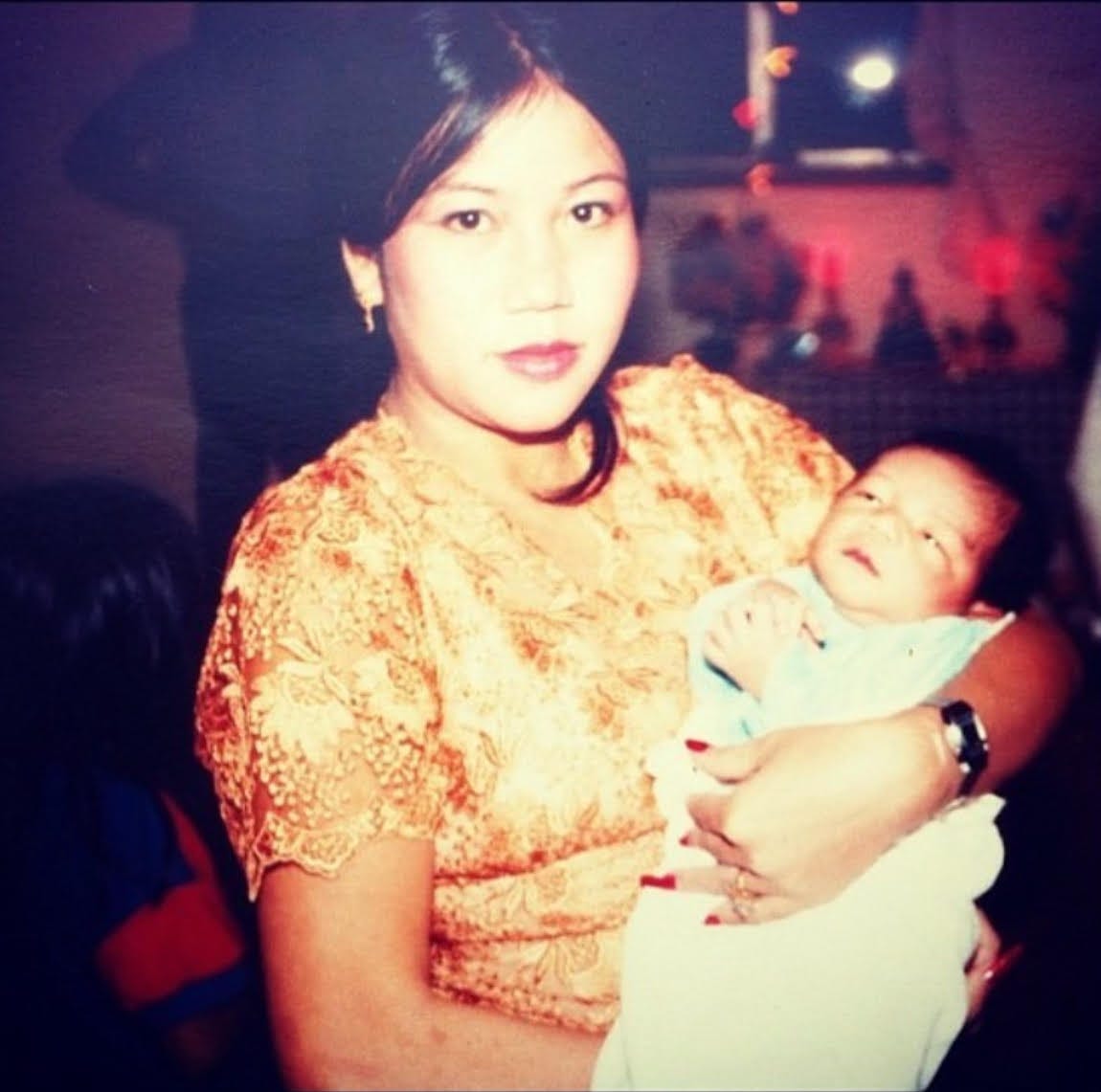

That’s kind of part of the reason I opened up Sophon because Khmer culture is traditionally so patriarchal. My brothers and I are really fortunate, our parents have had their differences, but they’ve remained together for a long time. They’ve gone through a lot of trauma. I wanted to create this space that not only honors our mom but also is an opportunity for me to give her her flowers while she’s still here.

This is my opportunity to not only honor her, but honor the women in the culture, and women in general. Oftentimes, we fail to remember that a lot of the foundation in most households, most organizations, most anything in society, the strength and the pillars are almost always around women. We often forget that just because history writes a society or culture as patriarchal, that doesn’t necessarily mean that’s always been the case.

Moms and aunties and grandmas are doing so much when they are balancing the home and work and all this and that too. They’ve been doing that for a long time.

OTTO: How has food played a role in the formation of your identity?

LONG: Food has always been something that has kept me close to my identity.

Growing up, I struggled with what it was to be American and Khmer. As the first child of refugees, I always wanted to be American, I wanted to be just like my classmates. I was a McDonald’s kid. I wanted to have that identity. But coming home, you’re speaking mostly Khmer and having that experience, it’s this seesaw back and forth. Going to elementary school in the early 90s and being picked on for what your parent’s packed you for food, it was always hard at that time.

You never really think about the fact that, not just in the nation but across the world, there are likely other kids that are experiencing the same thing in other capacities. Because when you're a child, you think this is only happening to you. You’re the only Asian kid in school, this is only happening to you. You don’t realize that you can take comfort, or I guess camaraderie or community, in knowing that others are going through this and within time, you’re going to find your identity.

Food always kept me close to my identity, even when I was unsure of who I was.

Even as I strayed as far as I could as a young adult, food was one thing I was always prideful about within my culture. I’d always love taking friends who were open or adventurous or never been to areas that were concentrated with Cambodians to try a lot of different things.

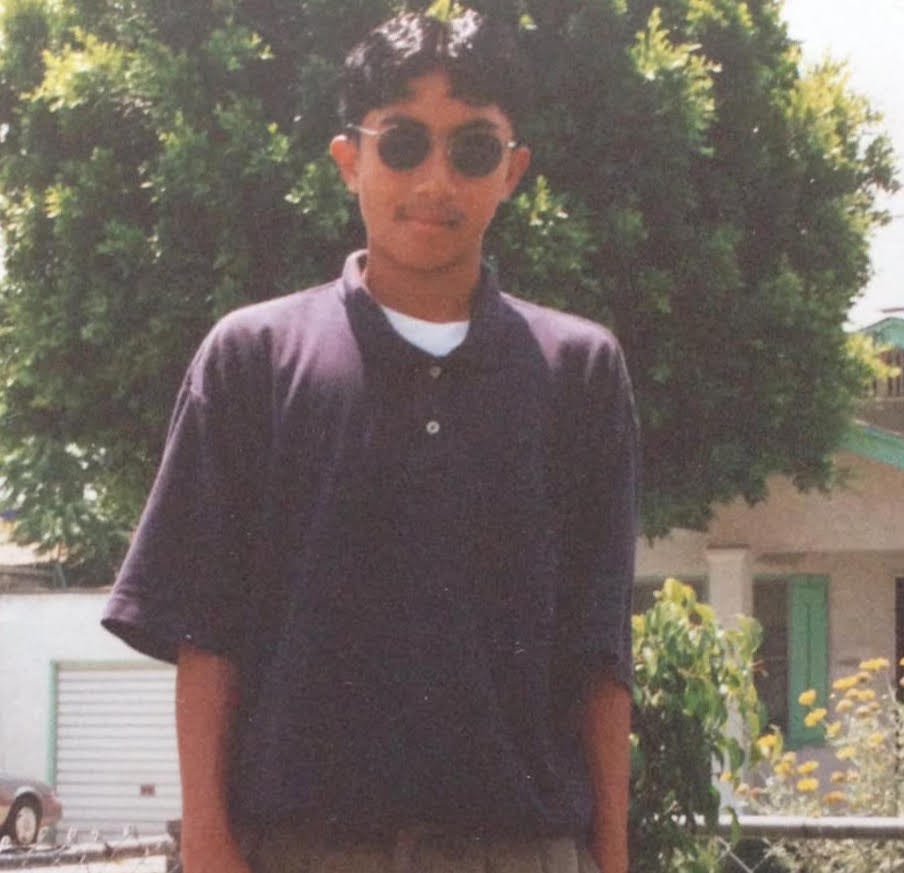

But my teenage years were really hard because I got caught up in gangs. I got caught in a lot of trouble and it was a moment in my life where I felt really disconnected to my identity and who I was because I felt like I didn’t have a place within my community. As I moved back to Seattle, this is really where I fell in love with who I was again.

Moving back [to Seattle] helped me grow closer to my family because I missed them. COVID pushed me to revisit this pop-up series that I did with my mom and my brother at Oliver’s Twist after I took over. It allowed me, forced me, to change the menu at Oliver’s Twist and we were able to try out the Cambodian menu.

It really brought me closer to who I was and made me fall in love with who I’ve become. A lot of the credit for that is always going to go to my mom and the culture—but also the community. Especially the adjacent community: Phinney Ridge, Greenwood, and the neighborhood surrounding Oliver’s Twist, the people that have supported us since the pop-up days. I feel like I owe them a huge amount of gratitude because they helped someone who was lost for a long time find who he was meant to be.

It means a lot to me and it is serendipitous that the space a few blocks north from Oliver’s Twist became available and Chris Navarra who owns Prost! was willing to give me the opportunity to jump into the space. He had other suitors, other interested parties, that had a lot more pedigree than I do on the culinary side and he turned down their offers to give me the space.

Food for me now is such a huge part of my identity because it’s the one thing that’s the glue to who I am, personally, and who I am with my family and my community.

OTTO: How has your narrative around food changed as you aged?

LONG: The narrative used to be so intimidating.

I feel like you don’t even necessarily have to be from another culture, everyone gets picked on for something growing up. You can get picked on by kids of your own culture and they can pick on you for the same thing they’re wearing or they’re eating.

But what [food] has done is change that narrative to feel like the space that I hold for myself is important, and it isn’t as intimidating anymore. What food has done is really created a sense of community where times have changed, where food is so comforting, food is so communal, food is—I hate to sound cliché but—a story.

When you really think about it, nowadays people are so interested in learning about and creating space for each other. That’s really important—when the narrative for food is that you can’t talk about food without involving the conversation of community, because food is community. You can’t have one without the other.

OTTO: You’ve shared a lot about your culture and how that influenced your experience around food growing up. What other variables in your life have profoundly impacted the way your relationship with food has evolved?

LONG: One of the biggest things that played into how that relationship has evolved is that the story of our culture and cuisine is still unknown to a lot of folks, so having to be an ambassador who tells these stories.

It goes back to what I mentioned when people ask what Cambodian or Khmer food is. A lot of folks have to preface the explanation with, “Are you familiar with Thai or Vietnamese food?” I wish that we didn’t have to preface it with that, but it’s so important because our food is so culturally and historically rich.

The Khmer empire was all of Southeast Asia for a long time. I use [Sophon] to create space to honor my mom and the women of the culture, where dialogue is available between myself and our guests. Most folks that aren’t familiar with the story, the history, are really appreciative to be able to come into the space and learn about it. That’s one variable that’s made food so important in my life.

Other variables would be, when I was younger, always feeling like a kid who was lost in what I wanted to do. I was the eldest of three boys. Our dad was a musician here and back in Cambodia. Our mom was a traditional Khmer ballet dancer. They had to hide a lot of their creativity and arts during the Khmer Rouge regime because if you were educated or creative or looked like a scholar or politician or anyone that they deemed intellectual, you were executed. They didn’t want any around to potentially plot against the regime. For me, that was such a huge variable for who I try to become throughout my life. Because my dad was a musician, I really wanted to delve into music.

At that time, I was studying jazz and took a lot of the traditional Khmer music and transposed it into jazz-style formats. My dream was to be impactful to the culture in that aspect. I lived in New York for a little bit and then moved back to California. When I moved back, I stopped delving into music. When I moved to Seattle in 2010, I got back into it again and found myself working in kitchens and restaurants and bars. That’s where I started to fall in love with the identity of our culture’s food, and food in general.

As I transitioned into restaurant ownership, bar ownership, I spent less time with music and more time with food. That’s where food just became so important. It became the new creative language for me.

OTTO: What has it meant to your parents that you opened Sophon and are on the path that you’re on now?

LONG: You know it’s funny.

When I was planning [Sophon], I hadn’t told my parents, but my brothers knew. Part of the funding process was seeding the money that we needed to open. I borrowed money from my parents but had to lie to them about it. They thought I was probably getting into trouble again and needed money to bail myself out.

When we were preparing to open, I told them [about the restaurant] and the reason why I was doing it. I want to honor them, honor our family, honor our culture. I want to create space for the culture because it’s so vastly underrepresented in the U.S. You [often] only find Khmer restaurants in Khmer communities.

They were really skeptical at first. They were like, “Why are you doing this? Restaurants are such hard work and it’s going to be a struggle.” I understood that but I had a couple things on my side. I had the opportunity to stay in the same community that was supporting me. I felt like I was filling a void that’s present in Seattle. And our story needs to be told.

They came for the soft opening and visited a handful of times the first couple months. When they really saw how the community was receiving it and how the staff was taking time to explain the menu, I think they really understood the grasp of what I was trying to do and they felt like it was more than just a restaurant.

Our then-pastry chef Theresa had been working on this mochi ball dessert and was so worried how it was going to come out. When I asked my mom and aunts for their reaction, they said, “This took us back to when we were in grade school in Cambodia and we got it from one of the street stalls.” When I told Theresa, she was in tears.

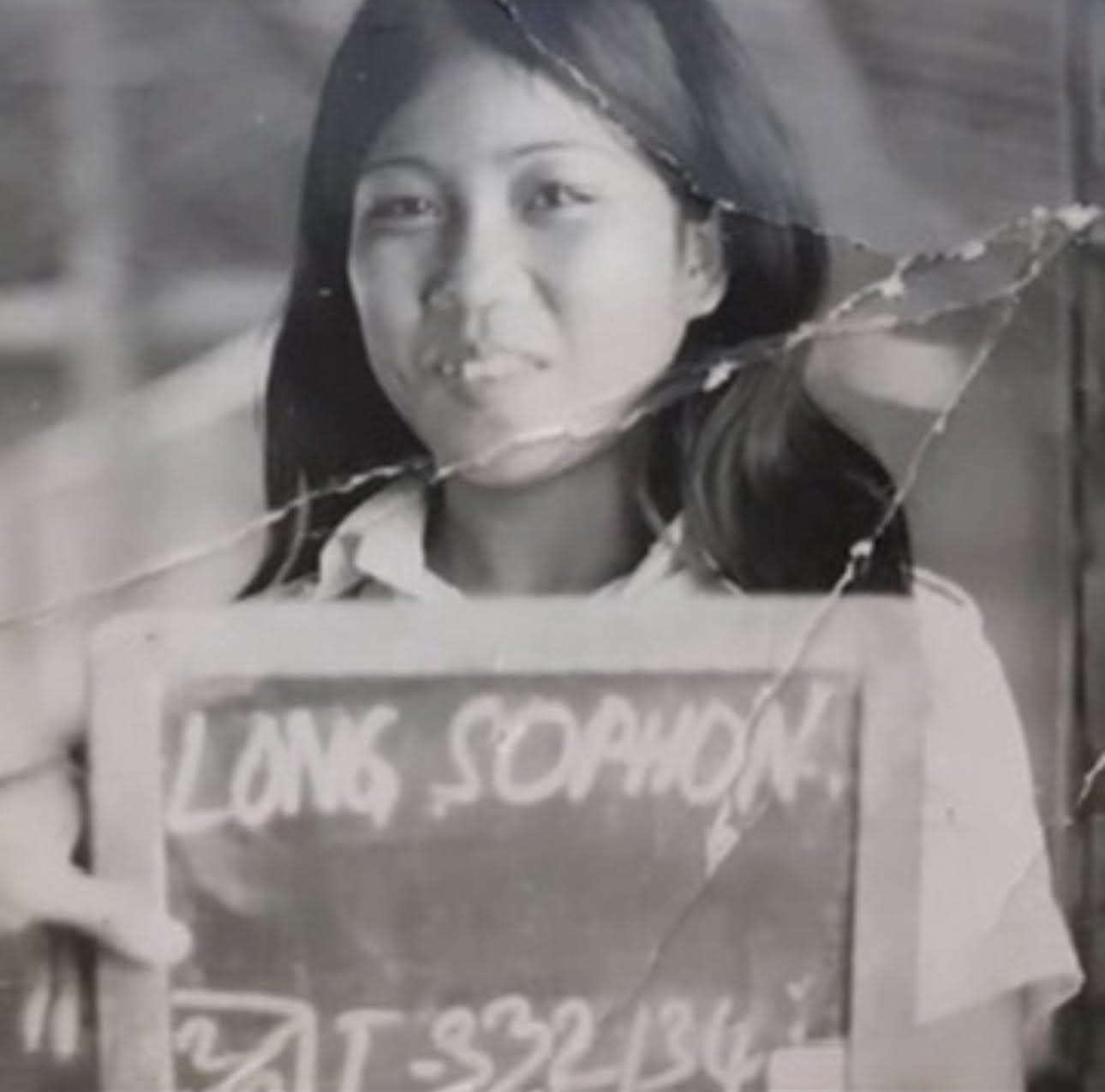

The walls along the side of the restaurant have our family photos. If this reaches anyone that is Cambodian, Cambodian American, or has Cambodian friends, I encourage [them] to email us at sophonseattle@gmail.com and send photos they are comfortable with. I will get them framed and put them up. I want to put up photos of people and their families, relatives, and distant relatives. I want them to walk into this space and feel like this space is collectively ours because we don’t get a lot of that.

OTTO: Like it’s their home too.

LONG: Exactly. I’ve been fortunate. The most rewarding thing is when people come in and say, “My mom passed a while ago, and when I had a bite of this, it made me feel like I was back in the kitchen with her.” That means a lot to me.

With all the praise we get from the community, whether they’re Cambodian or not and the writers and press, for me, I feel like we’re doing the right thing. It makes me feel like I was able to put together that right collective of creative people to be in this space that care. Not just about what we’re giving, but about the community as well.

I sat down with every single employee that we’ve had or still have—it was a long process—from the beginning and the thing that was always most important to me was community. I could care less about your background in this industry, but if you don’t have empathy or compassion or carry yourself with kindness, you’re not going to fit in this space. I need people that care about each other in this space and not just our staff to care about the guests that come in but the staff to care about each other. It’s what’s always been cultivated in our mom’s household or in her kitchen too.

OTTO: I would love to return to that younger you in the kitchen with your mom. Given all that you’ve shared about your relationship with food and how it’s changed you, what would you tell your younger self about that relationship?

LONG: With a question like that, I feel like everyone would look back and give sage advice. Say, to be confident. But I would say it’s okay to feel lost and uncertain of who you are because this process is going to help get you where you need to get to.

I’d be okay to just say, “You’re going to go through what you’re going to go through, just try to stay true to who you are and it’s okay because not everyone is going to see you the same.” All that shapes who you become.

OTTO: No one has said that before in these interviews. But it’s very true, and much easier to say that when you’re on the other side looking back. Now that we’ve talked about that past and present, what do you hope for as it relates to the future—for Sophon and your personal relationship with food?

LONG: I hope that I can continue to use Sophon and this opportunity to continue to grow and nurture our culture the way I think it should have been nurtured or accepted by our communities, not just in the country but across the globe too. I feel there is a sense of responsibility in that. For me, I would love to potentially expand the outfit and either grow another Sophon or different concept that is culturally driven down in Tacoma because there is a huge Cambodian community there, and continue to grow it in the Pacific Northwest because there isn’t a lot of representation. The sense of responsibility to keep telling the story is important to me.

Here’s what’s most glaring: Currently in Cambodia, one of the most prominent arts is bamboo-woven straw mats, made with bamboo and silk. A lot of those artists are now in their later phases of life and starting to pass on. But the younger generation wants to learn about everything tech-driven. [This art] is such a huge part of Khmer culture and it’s symbolic because, just like with food, many people in my generation and younger have become so disconnected from the culture or even their parents because their parents passed [away] early or they never cooked. So they never had the time or opportunity to learn the recipes and the culture within it.

It’s really important to continue growing these spaces because it gives the younger generation the opportunity to understand what they are possibly looking for too. That’s what I’ve been able to receive from a lot of folks in the younger generation: “I didn’t get the opportunity to learn this from my mom or dad or my grandma when I was younger, but being in this space has made me curious again.”

And if it’s sparking that curiosity, then we’re doing our job.

Ma’s Mee Katang

Recipe by Karuna Long

Serves 6 to 8

Many Asian cultures have their own versions of this dish—in other countries, it’s also known as chow fun or pad kee mao (or “drunken noodles”), among other names. However, this specific rendition is kind of the glue that kept me close to my culture for a long time, and especially to my family. Mom would always make heaping portions of it, since she raised three boys with insatiable appetites. Maybe it’s because she’s always been a phenomenal cook, even when we were little, in her twenties. Mom could make a portion of mee katang for twelve, and we’d easily polish it all off in less than eight hours.

Ingredients:

6 tablespoons oyster sauce

2 tablespoons palm sugar

6 tablespoons Golden Mountain seasoning soy sauce (divided as 2 tablespoons and 4 tablespoons)

2 teaspoon kosher salt

4 cups chicken broth or water

2 tablespoons cornstarch, tapioca starch, or arrowroot flour

20 to 24 ounces tri-tip or flank cut steak, thinly sliced

2 pounds gai lan (Chinese broccoli) (about 2 bunches)

6 tablespoons grapeseed or other neutral oil

10 garlic cloves, minced

4 tablespoons Shaoxing wine or sake

4 whole carrots, peeled, thinly sliced on a bias

24 to 28 ounces fresh wide rice noodles, soaked for 30 minutes in lukewarm water and strained before stir-frying (or dried noodles, soaked for 10-15 minutes in warm water) stir-frying)

4 to 6 eggs

Freshly ground black pepper (preferably Kampot peppercorns), for garnish

Directions:

Let’s begin with the gravy. In a medium bowl, combine the oyster sauce, palm sugar, seasoning soy sauce, and salt. In another medium bowl, combine the broth and cornstarch and mix well to make a slurry. Set both aside.

Place the beef in a medium bowl with a big pinch of salt. Toss, then set aside to marinate.

Trim and discard the tough ends of the gai lan stems. Peel the thick outer layer of the stems and discard. Separate the leaves from the stems, then slice the leaves into thirds and thinly slice the stems. Set the stems and leaves aside, keeping them separate.

In a large wok over high heat, heat 1 tablespoon of the oil. When the oil begins to shimmer, add the garlic and stir just until the garlic is light brown and becomes very aromatic, about 15 seconds. Add the sliced beef and sauté for about 5 minutes, until the slices are no longer pink. Add the Shaoxing wine and stir until evaporated, another 5 minutes.

Add the oyster sauce mixture and stir until all the slices of beef are nicely coated. Give the chicken stock slurry one last stir and pour it into the wok. Lower the heat to medium. Add the carrots and cook for another 5 minutes. When the sauce begins to bubble, add the gai lan stalks and cover. Steam for 5 minutes, then turn off the heat and add the leaves. The leaves may overflow and seem like they won’t fit, but push them down and they’ll settle in as they wilt. Cover and let sit until the stalks are easily pierced with a fork, about 10 minutes.

As the beef, carrots, and gai lan cook, separate the noodle strands and place in a large bowl. Add the seasoning soy sauce and toss.

Transfer everything from the wok to a large plate or bowl, then wipe the wok clean with a paper towel (or you can use another wok). Over high heat, add the remaining 2 tablespoons of oil and the noodles. Stir until the noodles have softened, then crack the eggs right on top. Break the yolks and stir the eggs with the noodles. Once the eggs are cooked, immediately turn off the heat.

Add the meat/vegetable mixture back into the wok. Give it a final toss to mix it all together and garnish with black pepper.

How has food shaped who you are? Share your story to be featured in an upcoming edition of Portrait of a Palate.

Thank you for being a part of this community. If you enjoyed this interview, please consider giving it a ♥️, let me know in the comments what struck you the most, or share with someone you love. Your support helps sustain my work.

"...a lot of folks don’t realize that Thai and Siam cuisine originated from the Khmer empire"

It's me, a lot of folks; super interesting read and thank you for sharing!